The Ismaili Center Houston’s architecture and gardens will set a new bar in a city increasingly devoted to modern design and lush green spaces.

With a structure designed by UK-based Farshid Moussavi and gardens by Thomas Woltz of Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects — a renowned landscape architect known locally for his work transforming Memorial Park — the new Ismaili Center will sprawl across 11 acres at the southeast corner of Allen Parkway and Montrose Boulevard. Ismaili Council president Al-Karim Alidina unveiled plans Monday afternoon at the George R. Brown Convention Center.

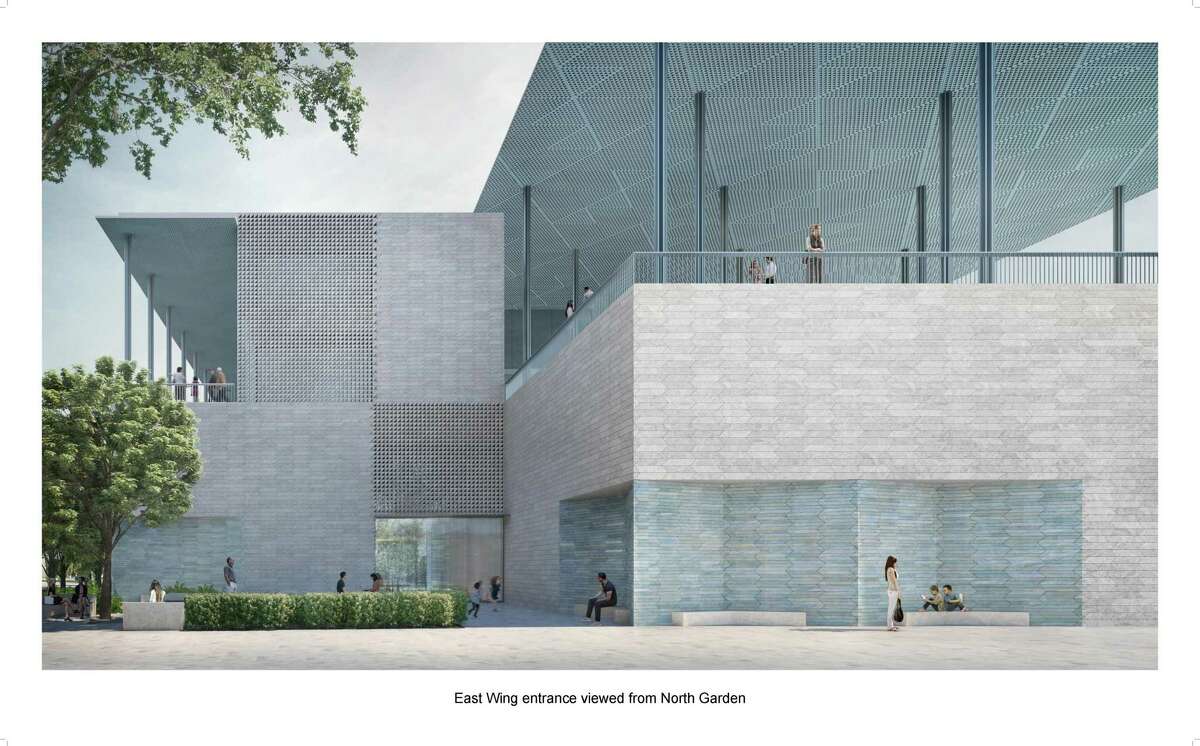

Clad in a Turkish marble, the building will be a cultural landmark where local and visiting Ismailis can worship, and where everyone can attend cultural and educational events. Gardens on all four sides will include terraced plantings and water features in a configuration that pays homage to ancient Islamic architecture but with vegetation found in Texas ecosystems.

“It will be an inviting space where everyone is welcome,” Alidina said.

Houston was chosen several years ago by His Highness Aga Khan as the site of America’s first Ismaili Center, picked for its large population of Ismaili Muslims and for its overall diverse community. The Aga Khan is the spiritual leader — or imam — of Ismaili Muslims, and is a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, who founded Islam some 1,400 years ago.

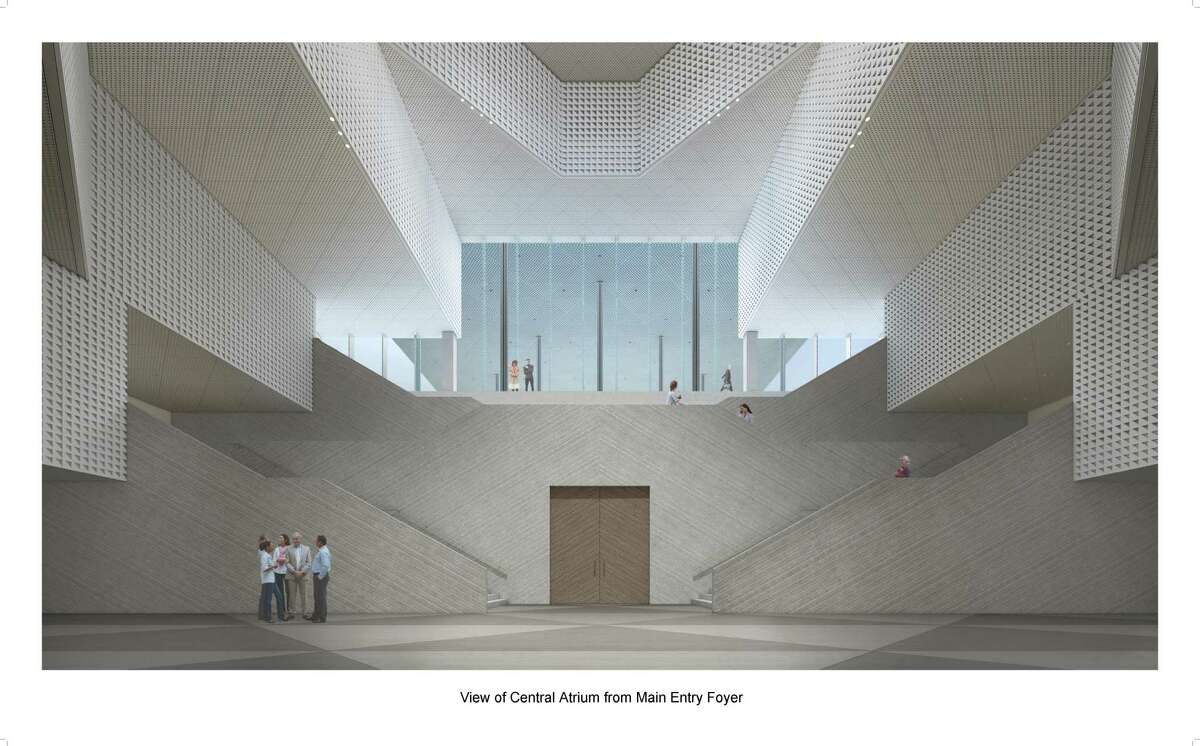

An artist rendering of the interior central atrium at the future Ismail Center Houston.

Courtesy of Ismaili Center HoustonThe Aga Khan Foundation purchased the local land in 2006 and later donated seven monumental artworks — Jaume Plensa’s “Tolerance” sculptures — that sit across the street in Buffalo Bayou Park. Excavation on the site is already underway, and a formal ground breaking will likely take place early next year with construction finished by the end of 2024.

Geometry in architecture

Moussavi’s design goal was layered: Create a building that pays tribute to ancient Islamic culture that will support modern life for 100 years. It needed to be an architectural jewel worthy of its spot at one end of a cultural corridor that runs down Montrose to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the Museum District.

“The Aga Khan has been a patron of architecture for many years. He is absolutely convinced and aware of the power of architecture to help people live a better life — that architecture is a force for good,” said Moussavi, a native of Iran who moved to the United Kingdom when she was 14 and was educated in the U.S. at Harvard University. “This is what sets the challenge when working on a building commissioned by him … every decision must be relevant and executed with excellence.”

It also needed to be a place where Ismailis could turn for spiritual solace, with a jamatkhana — or place of worship — where they could go for daily prayers. Social spaces would need to be used for cultural or educational events or even social gatherings, such as philanthropic galas or luncheons.

NEWSLETTERS

Join the conversation with HouWeAre

We want to foster conversation and highlight the intersection of race, identity and culture in one of America's most diverse cities. Sign up for the HouWeAre newsletter here.

“There cannot be a better moment to build this building. We have many different crises as humanity, including climate emergency,” said Moussavi. “The scale of the issues we face needs a collective response. It is about bringing people together to better understand each other and form a larger community.”

The building’s design includes stonework that appears as woven tapestries with breezes and light passing through. Stone screens in geometric patterns — squares, circles and curvy Arabesque shapes — are frequently used as ornamentation in Islamic architecture, which avoids images of religious figures.

There building will have several verandas, where people can be outside and still in the shade.

The Ismaili Center has no front or back; each side is equally detailed and welcoming, though there will be entry doors off of West Dallas and Montrose streets, Moussavi said. Deep on the lot toward West Dallas, the building had to be located outside of the 500-year flood plain to avoid damage in future weather events.

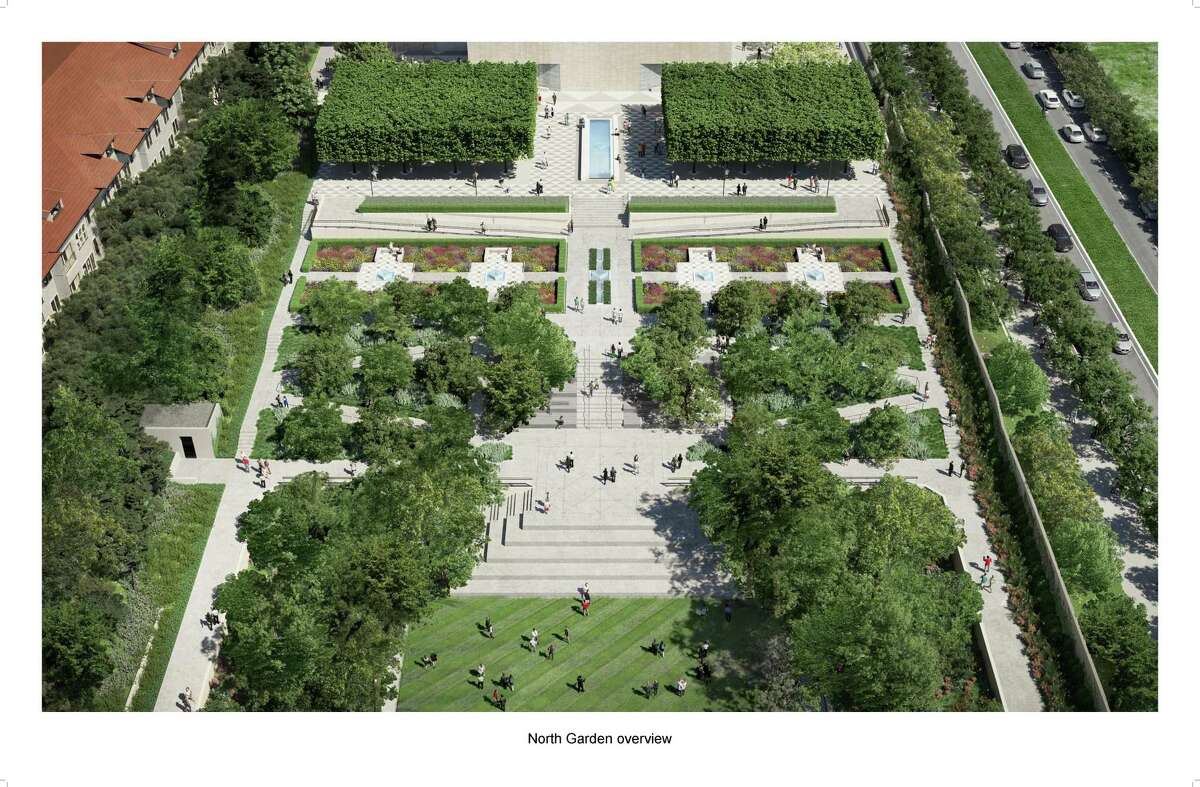

An artist rendering of the North Garden at the future Ismail Center Houston.

Courtesy of Ismaili Center HoustonOne form of paradise

Woltz, who leads the landscape architecture team that will craft 10 acres of lush garden where there is now dirt and scruffy weeds, also did the landscaping for the Aga Khan Garden in Edmonton, Canada. Houston’s center will be the seventh throughout the world; the others — built between 1985 and 2014 — are in London, Toronto, Lisbon, Dubai, and in Burnaby, British Columbia, and Dushanbe, Tajikistan.

On projects such as this one, buildings often sprawl across much of the available land; greenspace is treated almost as an afterthought. Not so for the Ismaili Center.

“The description of paradise in the Quran is a garden, and those descriptions have inspired more than 1,000 years of garden history,” Woltz said.

There will be a great lawn that can be used as an event space with 1,200 people seated or 1,600 standing, as well as plazas, courtyards and immersive garden rooms, each drawing plants from a different ecoregion: high plains, trans pecos, cross timbers, blackland prairie and Gulf Coast prairie. A bayou garden — at the lowest level and closest to Buffalo Bayou — will have native plants that are most resilient in case of flooding.

“This will be a different kind of formal garden than anything I know of in Houston. What other tradition of landscaping draws from Africa, Europe, the Middle East, Far East and South Asia?” Woltz said. “There are Houstonians from all of those places, so it stands as a symbol of that pluralism that also reflects the city of Houston.”

About the Ismailis

That Texas has the largest concentration of Ismailis in the U.S. certainly contributed to the Aga Khan choosing Houston for this project. Some 50,000 now call Texas home, and it’s estimated that there are up to 15 million in more than 25 countries in this sect of Shia Muslims.

An artist rendering of the future Ismail Center Houston, as it will be seen from Montrose Boulevard off of Allen Parkway.

Courtesy of Ismaili Center HoustonHouston has a handful of Ismaili community centers, all places with dual purpose, a jamatkhana where members pray and worship and where nonmembers attend events. Locally, they’ve hosted everything from food drives and blood drives to Ted Talk events and political debates, open to everyone.

His Highness Aga Khan is the faith’s only imam, and he’s expected to interpret the Quran with both literal and spiritual meanings based in current context. Local jamatkhanas have no paid staff and are run by volunteers he appoints personally. The faith stresses equality, so men and women are treated equally, and both are urged to have higher education.

Volunteerism is a tenet of the faith, and it plays out in big ways and small ways, too. For example, during prayer services, worshippers sit together on a carpeted floor and leave their shoes at the equivalent of a coat-check room. One any given day the volunteers watching over the shoes could be an 8-year-old learning to help others, or a doctor or investment banker.

After Hurricane Harvey, Ismailis rallied to help others throughout the city, earning the local faith group a Points of Light Award.

‘Building bridges’

Monday’s design reveal drew local dignitaries, and Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner was there via recording because he was called to Washington, D.C., for the signing of the federal infrastructure bill.

“My visit to the Ismaili Center in London … in the heart of the city allowed me to see the ways an Ismaili Center can help build bridges across communities,” Turner said. “The Ismaili Center Houston will also be a place where the city’s partners and stakeholders, public and private, can come together to discuss and solve the problems of our time.”

An artist rendering of the future Ismail Center Houston, a closeup of the building as it will be seen from the gardens on the Allen Parkway side of the building.

Courtesy of Ismaili Center HoustonPhilanthropy executive Ann Stern, president and CEO of Houston Endowment, praised plans for the new center.

“This will be a place for people to connect, understand differences and build bridges across all people and faith backgrounds and experiences. That is such a powerful thing, and never has it been more important than it is today,” Stern said.

And the importance of the 10-acre green space doesn’t elude her, either.

Some 15 years ago, a green renaissance began in Houston with the re-envisioning of the bayous, embraced as a place everyone could enjoy. From there, taxpayers and philanthropists have invested in better parks all over town.

“This is not just about creating green spaces and parks where people can walk with their kids. This is something that is very sustaining to people,” Stern said. “At no time did we realize this more than in the pandemic. That first summer of lock-down and work-from-home, seeing people in the parks and seeing how important green spaces are to mental health has changed our city in ways that we still don’t completely understand.”

diane.cowen@chron.com